Today, foreign English teachers in Korea must pass periodic HIV tests to keep their positions, and foreign graduate students may be disqualified from exchange programs and have government scholarships revoked if they are found to be HIV-positive. International human rights condemnation has not altered these facts.

In 2015, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination decided that Korea’s HIV testing requirements for foreign English teachers could not be justified on public health grounds and qualified as racial discrimination as most ethnic Koreans were not subjected to the same requirement. In late 2016, the National Human Rights Commission of Korea issued two decisions recommending an end to HIV restrictions on foreign English teachers and government-invited foreign graduate school scholarship recipients.

Former President Park Geun-hye and her government ignored all three determinations. However, the May 9 election for a new President offers an opportunity for a new president and government to revisit this issue.

Sadly, shortcomings in public education on HIV/AIDS remain a problem. As a result, many Koreans believe HIV to be far more infectious and transmissible than it really is and see a health threat that in practice does not exist. Contrary to the views of far too many in Korea, HIV cannot be spread through casual contact and modern medications can reduce the likelihood of transmission nearly to zero. Indeed, local health activists report that there are no known cases in Korea of a foreign teacher infecting a student with HIV.

As the Human Rights Commission recognized in its decisions, imposing HIV travel restrictions does not yield any public health benefit to Koreans. Advances in HIV treatment have vastly improved both quality of life and survival for people living with the disease, to the point that it can now be successfully managed with a daily pill. A recent study found that some people living with HIV in the United States “now have life expectancies equal to or even higher than the U.S. general population.”

Work and study restrictions on foreigners living with HIV may, in fact, have negative public health repercussions. By explicitly linking HIV to foreigners, these restrictions play a role in frustrating domestic prevention measures by suggesting that HIV is simply a foreign problem that can be addressed through border control.

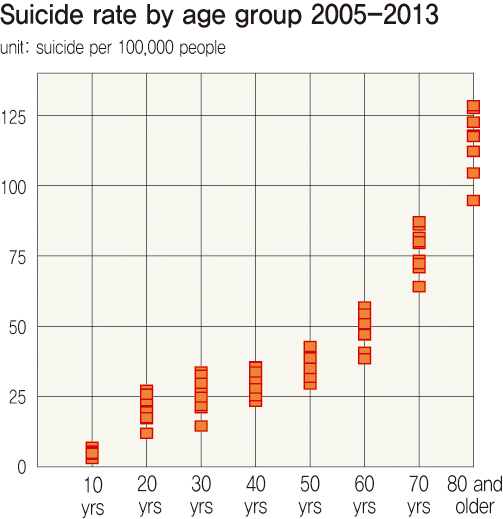

By strengthening the stigma against HIV, the government’s restrictions can also discourage HIV-positive Koreans from seeking treatment and contribute to fear of prejudice that causes many people to choose not to get tested for HIV — which increases the disease’s potential for harm. The stigma in Korea is so pervasive that people living with HIV are reportedly 10 times more likely to commit suicide than Koreans without HIV.

The World Health Organization announced that there was no justification for HIV-based travel restrictions in 1987, and in 2006 the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights and UNAIDS stated that the practice is “discriminatory and cannot be justified by public health concerns.” In 2012, UNAIDS and the Global Business Coalition on Health presented a pledge by the CEOs of 24 multinational companies opposing HIV travel restrictions.

Fewer and fewer countries maintain travel restrictions on people living with HIV. The U.S. did away with its travel ban in 2010, the same year the Korean government itself recognized restrictions as a form of discrimination. Korea went on to claim at the 2012 International AIDS Conference that it had rescinded all HIV-related travel restrictions on foreigners — even as it continued to require foreigners seeking work visas to undergo health checks that included HIV testing.

Put simply, the Korean government’s view and treatment of people living with HIV is outdated and contrary to internationally recognized best practices, and needs to change now. Preventing people living with HIV from studying or teaching in Korea may fuel xenophobia, does not protect Koreans from HIV, isolates and marginalizes people living with HIV, and perpetuates dangerous popular misconceptions about the realities of the condition. Korean officials should instead recognize that HIV is a global health problem to be addressed through treatment, prevention and education.

Korea prides itself on its technological leadership, and the issues in this presidential election center on modernizing political and business relationships. Instead of banning and shaming people living with HIV, Korea should promote public education about HIV transmission and treatment, improve access to HIV treatment, and combat the damaging myth that a HIV diagnosis represents a moral failure. And it should stop requiring HIV testing for foreign students and teachers.

*The author is the John Gardner Fellow for Health and Human Rights at Human Rights Watch.

Courtney Tran